Hop Along: 'It's Fun To Freak Out'

By: Michael Katzif via Soundcheck | Posted: June 9th, 2015 | Original Article

Frances Quinlan | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

It's practically impossible not to be drawn in by Hop Along's spiky and catchy melodies, or Frances Quinlan's distinctively frayed voice. It's the kind of voice that slides dramatically from scratchy intimacy one minute to intense howling into the night air the next. I first came across the band during a CMJ day party in the fall of 2013. On an especially impressive bill crammed with discoveries: Ex Hex played one of its first shows outside D.C.; a still-relatively unknown Torres tried out an edgier sound; and Courtney Barnett and Joanna Gruesome each won over fans during their first trips to New York. And sandwiched in between was Hop Along. Running through anthems like "Kids On The Boardwalk" and "Tibetan Pop Stars" from the its self-released 2012 album Get Disowned, I remember immediately thinking "Whoa, who is this?!?" as Hop Along played with staggering power and fun, winning over plenty of new fans -- myself included.

Looking back a few years later, it's striking how that one lineup showcased so many artists that have since grown to larger audiences -- or are poised for big years after putting out their best music yet in 2015. But where Courtney Barnett's rapid ascent feels like it came out of nowhere (or, Australia, technically) in part, thanks to her trademark song "Avant Gardener," Hop Along's trajectory has been more measured and longer in coming.

Starting roughly ten years ago as a solo songwriting outlet -- then called Hop Along, Queen Ansleis -- Quinlan crafted lo-fi folk songs while in art school in Baltimore, and released her first record, Freshman Year, in 2006. But it wasn't until she relocated to Philadelphia after graduation, moved in with and started playing music with her brother Mark that a full band began to take shape. There's a clear musical chemistry between the two siblings: His heavy and precise, metal-informed drumming serves as a counterpoint to her idiosyncratic singing -- creating an push\pull, quiet-then-loud dynamic that defines the Hop Along's explosive sound. With the addition of bassist Tyler Long and guitarist Joe Reinhart -- who came on as a full-time member after producing Get Disowned -- Hop Along grew into a local favorite among Philadelphia's supportive (and affordable) music community.

From the outside looking in, there seems to be something special happening right now in Philly; with bands like Waxahatchee, Swearin', Radiator Hospital, Girlpool, Nothing, and Cayetana (and many more) all having breakthroughs, the city is certainly enjoying a fruitful creative boom. "I would like to think these great bands would exist either way," Quinlan says. "There's not much you can do about where the spotlight is being turned." Still, Hop Along's hard work and word-of-mouth reputation is finally paying off.

Painted Shut -- the band's new album, and first on the beloved indie label Saddle Creek -- not only stands firmly alongside Hop Along's Philly peers, it's one of the year's best rock records.

Even as songs like "The Knock" or "I Saw My Twin" crackle and burn with distorted guitars and unrelenting drums, Quinlan's lyrics are heartbreaking and sincere -- scratching at personal anxieties and relationships, documenting the rocky transition into adulthood, and ruminating on indecision and fear of the unknown, all with microscopic specificity. Yet her words are so relatable that you begin to see something of yourself in her experiences. But where Get Disowned tended to look inward, on Painted Shut, Quinlan now seems to be tackling weightier themes.

Waitress

Throughout the album, she reflects on the lives of different characters as a way to illuminate ideas about love and loss, poverty and greed, and mental illness with honesty and in emotionally raw terms. And when told through tiny observations, conversations, and rich imagery, Quinlan often disguises meaning in elusive yet evocative lyrical phrases. "By the time it's old, a face will have been seen one and a half million times," Quinlan sings in "Waitress." "I would call you enemy because I'm afraid of what you could call me / The world's gotten so small and embarrassing."

"Powerful Man" -- perhaps the most immediate song on the album -- recalls a potent and painful tale of abuse, and the feeling of being powerless and unheard: "She didn't look too happy to see us / 'How should I know?' she said. / 'The man you just described could be anyone,'" she sings amid scorching guitar hooks.

Elsewhere, there are also moments of self-reflection ("We all will remember things the same," she repeatedly muses on "Happy To See Me") followed by displays of fearlessness ("None of this is gonna happen to me!" she chants on "Texas Funeral"). It's this blend of sweetness and fist-pumping, "let's-all-shout-in-unison" ferocity that makes Hop Along's music such a jarring and cathartic experience.

In a conversation with Soundcheck, Hop Along's Frances Quinlan reflects on some of her thematic inspirations, the evolution in the band's songwriting, what it's like to play in a band with her brother, and how she came to discover that distinctive voice.

Michael Katzif: Many of the songs on Painted Shut seem to be telling the stories of people who are struggling with depression, or being stuck in their own head. "Buddy In The Parade," specifically, references a relatively little-known musician suffering from mental illness. Where did you come across his story?

Frances Quinlan: The song is about Buddy Bolden. He was an amazing cornet player… during the development of jazz. He's referred to by some people as the "King of Jazz."

MK: During the ragtime and early jazz era.

FQ: Yeah. But there's no recording of his music. Later in his life -- in his 30's, I think, might be in his 20's -- he developed schizophrenia, to the point where basically he was in the middle of a parade, and was all dressed up, and he started walking the other way; he was frothing at the mouth. He just had a fit. His mother had to come get him. And from there he ended up in a sanitarium, [an] asylum until the end of his life.

After, he was buried in the poor man's cemetery in New Orleans. His sister couldn't keep up with the payments for the grave so they would just dig him up, make the hole deeper, and bury somebody on top of him. They did this so many times they changed the layout of the cemetery, or they lost the old papers keeping track of everybody and they lost track of him. They can't find him anymore. He's somewhere in Holt cemetery.

MK: How did this inspire your song?

FQ: I was acquainted with somebody who had schizophrenia, and for some reason that meeting stayed with me. I certainly take my mind for granted as my identity. I assume I'm me always. But I don't know what could happen [if] all the little ticks that I have got a hundred times worse. And who I am then if a part of my brain deteriorates or I have an accident and something happens? A lot of us aren't equipped to deal with [that] after they change, and it's not their fault. I mean, there's so many; I'm sure there's so many mentally ill people in the world. Because this happened in the early 1900s and even now we're not equipped to help people properly.

MK: Similarly, "Horseshoe Crabs" mentions a song by Jackson C. Frank -- a folk musician who inspired and was covered by many musicians like Simon and Garfunkel, but sort of disappeared. There's a line about playing one of his songs...

FQ: That's him. It's actually about him.

MK: So Jackson Frank is the character in the song; you're singing as him?

FQ: Yeah, Jackson C. Frank was homeless for a long period of his life. He was older then, I'm not sure his age. Basically, a college student came upon him and helped him out for a while. And at one point they recorded him, but his voice was so shot by then by the medications he became really overweight. One of his recordings when he's older is one of my favorites -- "Tumble In The Wind," I believe, is from that rough point in his life. But he tried to play "Blues Run The Game" and he could barely play it. It was really sad, what I read about it.

MK: To me, the songs on your first record, Get Disowned, felt like they were grappling with internal themes. They were songs about you. Now with Painted Shut, your lyrics still feel deeply personal, but also seem to be painting these vignettes about characters, different places and time periods as a way to tell stories about larger macro issues. Did you feel your songwriting evolve?

FQ: Exactly, because my internal issues kind of remained the same for years and it gets to a point where, how many times I'm going to sing about how guilty I feel all the time. [laughs] We're all proud of Get Disowned, but lyrically there's a vagueness to it because I was younger and trying to write from my experience. I feel in some cases, I wasn't quite ready to.

The songs I feel most proud of on that record was the songs where I was the most blunt. A song like "Trouble Found Me" is a very clear picture of something that happened.

Trouble Found Me

MK: "Laments" is like that, too. It's this honest depiction of two people in a crumbling relationship, deciding to split up their things, and ultimately, it's about the inevitability of either staying together and getting married, or breaking up because it's not working. And it's cleverly narrated by this old mattress that's observing from the outside. The lyrics have these little snippets of conversation that are so specific, it's completely universal and relatable.

FQ: Thank you. I wrote that song when I was 18. I think it's funny that I was a virgin when I wrote that song. And it's all about sex. I feel like until I lost my virginity, all my songs were about sex. Not really, that's not true.

MK: I think that's probably true for a lot of people.

FQ: Who knows. [laughs] When I was younger I definitely had stronger ideas about things. That's certainly -- oh God, it's like that Bob Dylan song, "I was so much older then, I'm younger than that now." ["My Back Pages"] It's true. I was very confident to sing about marriage when I was 18 and had no idea what I was talking about.

MK: So how do you feel you've grown as a writer?

FQ: I like to think that I'm always trying to improve as a writer. It's always a challenge. There was a lot more editing of the lyrics on this album than I think I ever done. And a lot more parting with lines -- even whole songs -- because it's too vague, or it doesn't have the weight to it.

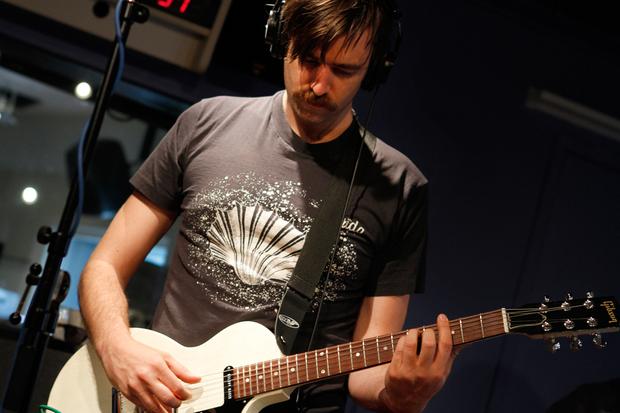

Hop Along's Joe Reinhart performs in the Soundcheck studio. (Michael Katzif / WNYC)

MK: Hop Along originally began as a solo thing for you. As the band has grown to include Mark and Joe and Tyler, has the songwriting process become more collaborative? Were you more consciously writing these songs with the band in mind -- or thinking about how songs might work in the live set?

FQ: Absolutely. Everybody in the band is incredible. Pat on the back there to myself, too. [laughs] There's no way I'm going to write any of the parts that Tyler, Mark, and Joe come up with. We were practicing without Joe the other day -- he had to leave -- and it was such a drag. We're a unit now. Get Disowned was like that because the group was just joining. Tyler was actually the producer of that album, so he had a lot on his plate. And Don was still playing guitar, and Mark and I were getting to know each other.

I just think some bands take a long time to understand each other. Even now, we argue. Everybody is coming from so many different places, but that just means they have more to offer, and it keeps it from being stale or overdone. I think we're kind of a weird band and I really appreciate that.

Hop Along's Tyler Long in the Soundcheck studio. (Michael Katzif / WNYC)

MK: Nearly every song on Painted Shut is more explosive, the melodies are catchier, your singing is bolder, the sound is noisier. To me, it's the sound of a band coming into its own.

FQ: Absolutely, I think they're bringing themselves into it. Everybody I think loves their instrument in some way, and if you have that love for what you're doing you want to give yourself to it I think everybody is writing their parts and they're interesting. And even if they're simple, that's a compromise too. When you have to say, "I want to go crazy."

It's funny: this album is my attempt to rein my voice in a little, because I know it's kind of insane sometimes and that's been a challenge because it's fun to scream. It's fun to freak out.

MK: So by editing and pulling things out, there's more space for things to happen.

FQ: There's a conversation happening. You're not opting out. You're not exiting the song by stripping the part down, you're just making room for something to happen. And we really we're learning to do that with this record.

MK: Is this the first project you and Mark have played together? What's your dynamic like as sister and brother working in a band together?

FQ: I don't think I met siblings yet who get along perfectly, and when I do, I kind of give them the stink eye. [laughs] [We've] known each other since I was born, so it's beautiful and really deep. But when we were younger, we did not agree about anything music-wise. Except I would pick up stuff while he was discarding it. He was definitely the older brother that showed me what was cool.

MK: What kind of music did he introduce to you that you liked? Did he ever play anything that you thought "This does not appeal to me at all"?

FQ: I don't want to diss my brother from high school. [laughs] Cannibal Corpse. I couldn't roll with Cannibal Corpse. He didn't push that stuff on me, he's just like, "I'm listening to this and I'm going to listen to this loud." And you know, I respect that. [laughs] I was listening to Jewel and Natalie Merchant, and Fiona Apple, and Ani DiFranco. Actually my oldest brother showed me a lot of female artists. When I was turning 16, Mark gave me Pedro The Lion's Control and it became one of my favorite albums. That was the first thing where we were like, mutually, "This is a great band."

Hop Along's Mark Quinlan plays in the Soundcheck studio. (Michael Katzif / WNYC)

MK: How did your different tastes affect the music you make together as Hop Along?

FQ: I think it's cool that we're so divergent when we were younger because I just think the drums are such an important aspect of our band, any band. I think most people watch the drummer more than they realize. Mark has such a fresh take on what would be interesting -- and he edits too. We all have to edit ourselves. That's the biggest challenge in our band because of how different we are we all have to compromise, but where we all meet is really fun in the end. Mark and I agree a lot more on music now. We're a lot more mature. We don't just say "This sucks" when somebody puts something on -- and I appreciate how open he got me to be to listening.

MK: Did working with a producer like John Agnello help that editing process, too?

FQ: Having John there was a amazing. He was essentially the fifth member of the band. He had great ideas, but at the end of the day he was like, "It's your band, do what you want." But having him there, he was cheerleading for us a little.

MK: It's always great to have that outside person to say "This is good, move on," or "Work on this."

FQ: When you love your instrument you can be anal about it. I would say most of us are pretty much anal about it. I'm not so much about my guitar. I'll say that "That's fine." But vocally, I lose my mind.

Hop Along's Frances Quinlan sings in the Soundcheck studio. (Michael Katzif / WNYC)

MK: You do have this very powerful, distinctive voice: It's got this full range -- sometimes scratchy, sometimes you're almost howling, yet you can be very quiet and pretty, too. Who did you turn to for inspiration in singing?

FQ: Well, I always loved women with big voices. It's funny. I'm drawn to women with big voices and men with small voices, at least it seems that way. My mom had Aretha Franklin albums, so I would listen to those. Billie Holiday. She wasn't a screamer but she had an interesting voice.

MK: Well, she had passion there. I can hear that passion in your voice, too. I hear the desperation, I can hear the pain.

FQ: Thank you. I think there's something amazing to be able to convey something with subtlety. And it's something that I always struggled with. Conveying with subtlety. Nick Drake does it. He has so much character in his voice, too. But even the drummer of Velvet Underground -- Maureen [Tucker]. Even a song like "After Hours," [sung by] Nico. You know, there's something really great about being able to be quiet.

But there's also something so fun about losing your mind. I love Sleater-Kinney. I picked up a Sleater-Kinney album when I was 15 and I freaked out about it because I never heard women sing like that. I was late to a lot of stuff. I came to the Pixies when I was 15 -- which I guess isn't that late but people are always like, "I heard this band when I was 12." I do love a variety of things.

MK: Do you feel like your voice is still evolving?

FQ: I'm really still learning about my voice. It's so interesting when you hear artists who kind of found their way later on in their life and they have older records and you can hear them searching in those records. I love Lucinda Williams' albums in the 90's -- but she has older records in the 80's, and I feel like I can hear her looking. Maybe I'm still looking.

MK: Is it just frayed at the end of the tour?

FQ: The road is definitely doing something to it. I find that the first week is a little rough but by the middle I'm good. I always get sick at the end of the tour. But I just feel that I'm getting older and haven't like played in dirt in a really long time. That's what I think keeps your immunity up.

MK: Philadelphia is having this moment as a breeding ground for artists with a DIY work ethic or aesthetic. As one of those bands, do you get that sense of community?

FQ: Thanks. I don't want to say thanks, I had nothing to do with [it].

MK: Well, you've been around a lot of those musicians, I'm sure.

FQ: I'm lucky that I moved to Philly. I came kind of late, honestly. I moved there in 2008, and I'm just grateful that it was so welcoming. "Oh you just moved here? Here's a house. You can play here." I would credit that to the people that brought it there in the first place. I think what I really appreciate in a city is when it's helping itself when nobody else is paying attention -- and I think that's been going on for years before.

I can't tell you when that happened, but when I moved there, there was this warehouse of artists getting together. I had no idea that there had always been artist communities there. I put on a house show in 2006 at this place called Veggieplex, this punk spot that was a long running base in West Philly, and it was great. I thought they they were great. But now, there are house shows that pop up everywhere. As soon as one shuts down another one opens up. And they're great. And people are more organized it seems like.

The forming of it, it's like New York in the '70s. There was this great community there in the '50s that built itself up and had these shows in lofts because they wanted to and cared about it. Then give it ten more years and people who heard about it and want to be a part of it and that's a great thing that happened. We had artists like Patti Smith because of that.

I don't know, it's just getting noticed right now, and I'm so happy that it is. But it does make me think of those bands when I first got to Philly -- and some of them are still bands and a lot of them aren't. It just was a really welcoming community. People from New York came down. Also money is a huge factor.

MK: It's actually an affordable city to live compared to New York or even Washington D.C. That's why Baltimore has been such a thriving place for all the artists and musicians.

FQ: I lived in Baltimore. Absolutely. Baltimore is another great example. The people in Baltimore that want to make things happen make things happen themselves. It's not as sprawling as Philly is, but it's strong -- [like] Wham City. Lot of great artists [are] still in Baltimore, too. Baltimore is such a real place to me. I don't meet too many transient people. It's a really strong community. It's a smaller city, so you can be aware. I [saw] a lot of people that I know in Baltimore posting pictures of the protests; they're there and concerned. And I think that's another beautiful community.

Hop Along performs in the Soundcheck studio. (Michael Katzif / WNYC)